What is market risk? Complete Guide

When a market bear strikes it’s practically impossible to gather enough time to grieve your losses.

Without market risk, there is no investment. If someone misjudges the dangers of a market bear, they might as well lose everything. That is what we saw in the financial crisis of 2008, and it is still the case today if one holds himself to account. When a small investor does this, it’s unpleasant, but if it’s a big bank, it can be a disaster. Market risk is one of the biggest financial risks and we are here to help you understand the basics. We’ll go through exactly what it means and how it’s generated. The focus of our article is on banks, showing how they quantify this threat and what regulations apply to them.

The Bear

The period 2007-09 taught many that the market bear is no spoof or joke. When stock market prices and OTC fell like dominoes, the world turned upside down. But it doesn’t even take a financial crisis to burn ourselves with bad exposure. Market risks can come in many forms, and often very unexpectedly. This was the case, for example, with retail foreign currency loans (with a debtor’s eye), where masses went into credit transactions without knowing the existence of foreign exchange risk. It was a painful lesson for many.

“Of course, it wasn’t just the public who were wrong at the time, it was the banks and regulators,” he said. Indeed, in the great financial crisis, it turned out that market risks were being measured inaccurately and were poorly regulated.

In this article, we will now continue on the topic of financial risks and deal with the measurement and regulation of threats arising from market movements after credit risk. Again, we are doing this from a banking point of view, as these are the protagonists of the financial world. Plus, it is the banks who are most likely to be able to manage market risks well, because if they do not, they would put our money at risk.

What is the risk here?

Let’s start with a tour of the concept. Market risk involves an adverse change in the exchange rate or implied volatility of financial products. Simply put, it seeks to capture the risk of loss due to the entire market or specific market exposure. It is no coincidence that we are wording a little carefully here. This is because the literature divides market risk into two main components; The first is general market risk, which includes the risks specific to the market as a whole. This risk cannot be diversified, although it can be protected against it by using special cover techniques. A good example is when stock market indices all start to fall in the market, and even though we keep a lot of different stocks in our portfolio, we still suffer losses.

https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs159.pdfThe other component is the specific (unique) risk associated with the closer product, such as a particular share or a specific bond issuer. This is already a diversifiable risk, but there is not always a business need to defend ourselves against it. It is worth noting that there is even some credit risk and migration risk deep in the market risk, as we give and take shares with great intensity in vain if their issuer suddenly goes bankrupt or their credit rating changes. In such cases, a serious loss can always arise. This was therefore particularly taken into account in banking regulation when a framework for market risks was developed; For example, the IRC calculation was born, which in English stands for Incremental Risk Charge.

Market risk may arise in many cases, but regulation focuses mainly on financial products held for trading purposes. The basic premise behind this is that if we keep something in our book until maturity, not for trading reasons, then it is worth applying the credit risk framework there. After all, it basically doesn’t matter how, for example, a bond’s price develops when coupons are paid out without any problems and the transaction expires without any problems.

The area of market risk should therefore be narrowed. The Basel guidelines state that all fixed income and equity exposures in banks’ trading books should be included. Moreover, we also include foreign exchange and commodity exposures in the bank’s complete Trading and Banking Book. Due to the latter, it is otherwise quite rare for a banking business mix where there would be no market risk and no RWA or capital reserves would have to be created for it. Even if the bank does not have a trading book anyway.

What is a bank doing on the market?

To understand the topic, let’s get a little more into what this aforementioned ‘trading book’ means. To do this we will take a closer look at what banks are doing on the market, which exposes them to market risk and special regulation.

In addition to their role as money creators and creditors, banks occupy a key position in financial market and capital market intermediation. It would be reasonable to say that they are the selling side of the market, because in many cases it is really thanks to them that some products and securities have a market at all. In OTC markets, such as the foreign exchange market, banks play a decisive role and without them we would live in a completely different world. But there are a lot of misunderstandings and malicious assumptions about what exactly a bank does on these fronts.

With our previous statement in mind, we find it important to remind you to not forget that the market presence of banks is not focused on speculation, but on mediation and the provision of services.

U.S. big banks have also been banned from trading their own accounts (proprietary trading) by adopting the Volcker rule. This type of activity has not completely disappeared from the banking world, but a significant transformation has taken place. From the global big bank, these divisions, as well as the star investors working there, have emerged and established hedge funds. Thus, in this form, own-account trading has not been lost on the economy, only the circle of risk-bearers has been transformed. The latter is therefore correct, as Paul Volcker and other prominent economists have argued.

Even if international banks no longer take market positions for their own gains, they will still remain very active in the market due to customer needs. This is because of the so-called market making and brokerage activities.

This is in reference to when the bank’s traders trade or hold securities to meet customer needs. For example, a customer can ask the bank to acquire XYZ’s hard-to-buy shares on the OTC market. Or the bank may decide to buy in advance from that XYZ paper due to expected customer needs. Moreover, you can build such large portfolios from such securities that your clients can then sell and buy at any time.

In the case of the former two, the bank receives revenue from a certain percentage of the transaction fee, and in the latter line-up it makes a profit on the difference between the buying and selling rates

From this we can see that a bank doesn’t play directly to make exchange rate gains on securities, but it still exposes itself to market risks in the same way.

This is a typical business setup for banks, and is what can lead investment banks to face very significant market risks.

The rules of market risk

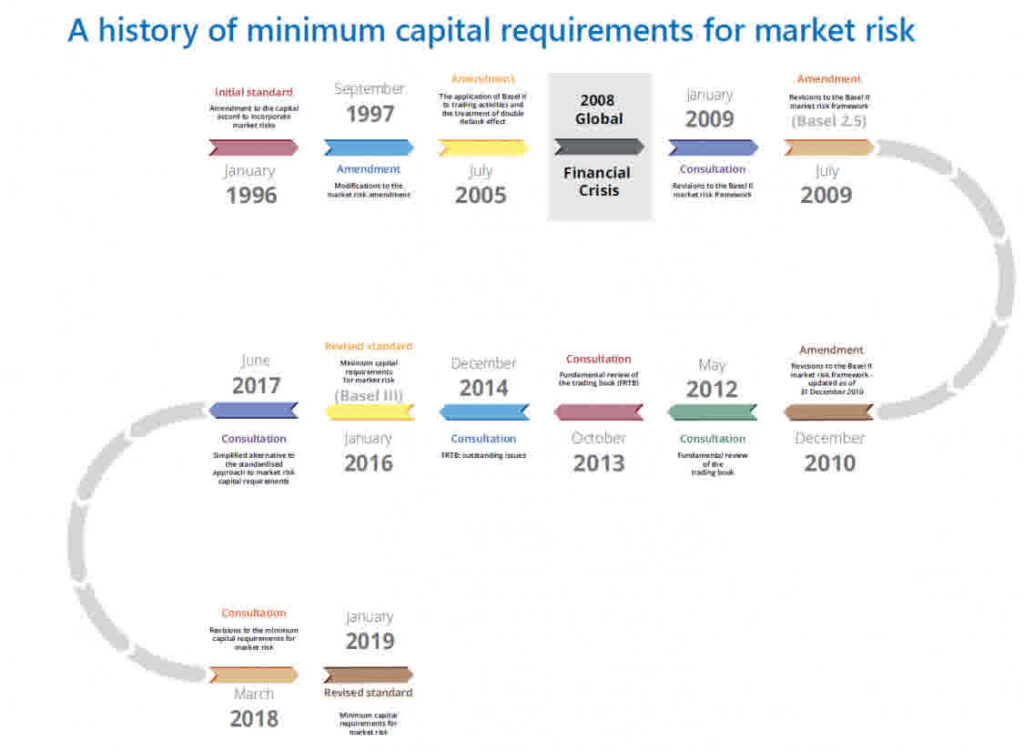

It is of the utmost importance, both for the well-understood interests of the bank and for the regulator, to quantify these risks. Unfortunately, the financial crisis of 2008 highlighted the lack of a Basel 2 framework, which was ironically designed for this purpose.

In response, the so-called Basel 2.5 guidelines were established as a rapid remedy in July of 2009, which significantly increased the capital requirement for market risks. But that wasn’t enough. So, in 2012 a thorough rethinking of market risks began, which the industry called the FRTB (fundamental review of the trading book). This comprehensive study transformed both the standardized approach to market risk and its quantification with internal models.

Banking regulation never happens overnight, it often takes years for impact assessments to be carried out. In addition, the banking sector will still need to be consulted afterwards, and individual states will have to legislate. Moreover, after that, banks even need time to prepare and adapt. It’s understandably not easy as any substantial change here will always take years to be considered to be a positive success.

Thus, it is not surprising that four years after the start of FRTB consultations, the framework had only just been re-amended in 2016. Nor is it that the rules need to be further refined, and in 2019 the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) announced new changes. This latest guideline finalised only Basel 3, the European introduction of which has only just been discussed with CRR2.

In short, it was a long birth by the time the market risk framework was born, which we can read today and which is intended to ‘finally’ address the lessons of the financial crisis.

How does this system work?

We cannot compress all of the countless essential points of the market framework into just one article, but we have summarized its most important pillars and the risk measurement is explained a little better below.

As with credit risk, the starting point for measuring market risk is that banks either use their own model to calculate risk-weighted assets (RWA) or follow a standardized approach. Here again, the idea is that through their own internal models, banks will be able to assess actual risks more accurately, as they only really know their products and they can see up close what losses their market business has suffered in the past. At the same time, the regulator needs to set minimum requirements for models and or modeling to make it work well. The standard method should be a credible basic method at all times, where the risk from each product is quantified with sufficient sensitivity.

However, in addition to defining the methodology, the regulator should also address other issues. A key issue is that the bank correctly defines the actual range of products (the trading book) that fall under the market framework. The possibility of the bank abusing the classification should be excluded from the possibility of artificially lower capital requirements. The latest regulation therefore strictly stipulates this, and if one exposure is transferred from one book to another – say, from trading to banking – then the bank should not have a reduced capital requirement.

Finally, it is even necessary to regulate when banks’ models perform reasonably in measuring risks. This is also a part of the market framework that has received considerable attention in recent years, as many models failed in the 2008 crisis.

The four themes are the cornerstones of the market risk framework. Themes are as follows; Internal model measurement, standard method measurement, model validation, and the definition of the trading book.

In this article we will go deeper just into the topic of risk measurement. In particular, we only look at the basics of the most common VaR-based modeling. This method is a very nice and relatively new scientific direction in quantifying risks. There are problems with this, of course, which the regulators have discovered. These will be discussed and summarized in the remainder of this article..

Modeling market risk

The so-called Internal Modeling Approach (IMA in the literature) is currently based mainly on various applications of VaR (Value-at-Risk). This is about trying to estimate the frequency of the distribution of gains and losses (P&L) and then shooting the risk profile of a product or portfolio based on the area under the curve. In this way, it is possible to say the probability of a given loss occurring in the examined period.

Looking at a portfolio, we can say what is the maximum probable loss we can have in the coming days or months. If, for example, the 30-day 1% VaR is usd 10 million, this means that we have a 1% chance of making a larger loss in one month. On the other hand, out of 100, we will only face a loss of less than 10 million in 99 months. This value of 10 million can be obtained by estimating the density function of a given portfolio, from which the value at 1% can be obtained directly.

VaR is an extremely popular and very widely used method of assessing the maximum loss that can be made in a bad month, with a given confidence in the results.

There are several ways to model a risk value, but three main groups can be identified. The simplest variety is the variance-covariance method, for which it is enough to estimate the average change and standard deviation. Much more work is needed by the historical method, which reconstructs the actual distribution of gains and losses from past data. The most complex method is the Monte Carlo simulation, in which a separate model is responsible for future outputs, such as a share price. This really has an advantage if we can really capture the characteristics of a product’s exchange rate turf and simulate it by simulating it to generate a P&L distribution that is more authentic than the historical method.

This is no easy task so, unsurprisingly, the vast majority of banks follow the Historical VaR Approach.

The regulator, on the other hand, can penalise inaccurate models by setting VaR multiplication factors, thus encouraging banks to choose the best possible solution. How successful this is in practice is already the subject of a separate professional debate.

VaR calculation, regardless of what method you choose, has several limitations. One of the most important is that if we do not have enough information about a financial product, we cannot monitor its price regularly – therefore it cannot be modeled properly. When this is the case, VaR calculations are not actually able to capture market risk well.

The other problem stems from the realisation that market losses have a particularly cruel nature. The edge of loss distributions often crept upwards, that is, it does not behave according to the normal distribution. This means that very large losses are not necessarily so rare, but it is very difficult to see. The VaR calculations used in practice can easily underestimate the value actually at risk, and the 2008 financial crisis was a disrepute example of this.

The banking industry has come up with several ideas to compensate for this. For example, it has invented the stressed VaR calculation (SVaR), which calibrates the quantification of risks to adverse market conditions, thereby helping to define the overall market RWA and capital requirement more accurately (and higher).

But the latest regulatory approach goes beyond that and introduces the so-called conditioning VaR (CVaR), commonly referred to in the industry as ES (Expected Shortfall). The essence of this is to try to capture the average of the margin of loss distribution. So while the VaR of 1% says that the worst 1% of the distribution has a limit of this size, the ES tells us how much loss is generated on average in the area below the 0% and 1% curves. If there are good high values at the very edge, then the ES will significantly estimate a higher risk than VaR. This solves a major shortcoming of previous VaR modelling practices.

The important difference between the VaR and ES methods is how it captures the edge of the distribution. Source: Bank for International Settlements

Basel 3 – The end of a long journey

Market risk regulation is no longer content with banks meeting the regulatory requirements once their internal models are introduced. Instead, the BCBS recommendation requires continuous retesting of models (This is known as a backtest requirement).

As soon as the supervisor finds that the model used in one of a bank’s trading business is not performing well, i.e. the estimated losses are significantly below the realised level, it may suspend the model use licence. In this case, the bank should return to the standard method, which usually leads to a higher capital requirement.

But the regulator doesn’t even stop there. Under the new recommendations, the difference in capital requirements resulting from internal models and the standard method will be increasingly limited. This will eliminate the need for VaR or newer ES model variants to underestimate market risk and thus reduce the capital that is trained on it.

If we had known the interpretation, the measurement method and the regulatory method, as described above, before the financial crisis happened, we would probably be a few steps further ahead.

However, the problem of measuring and regulating market risks is very likely that the finalisation of Basel 3 (which many people from within the banking industry are already calling Basel 4) is not over. Financial products have evolved enormously over the last few decades and we have seen a new face of market risks in the last few crises.

It is almost impossible that, as financial innovations progress, there will be no need to further clarify the practice of measuring market risks and the related banking regulations. Of course, it’s also a big deal that we’ve come this far, and the banks have become much safer.

Read more from Us